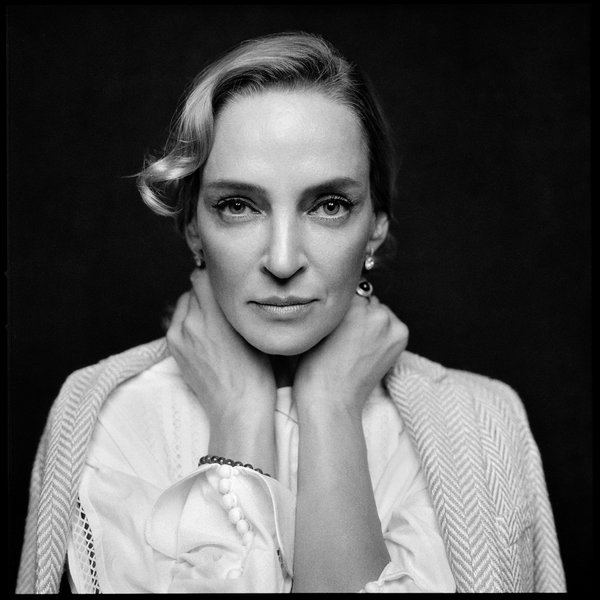

Artist Neda Kovinic just came back from a residency in the South of France and is already getting ready for a meeting in Salzburg. We discovered Nada’s art at her solo exhibition I am black, but beautiful, shown in the Remont gallery in Belgrade this spring.

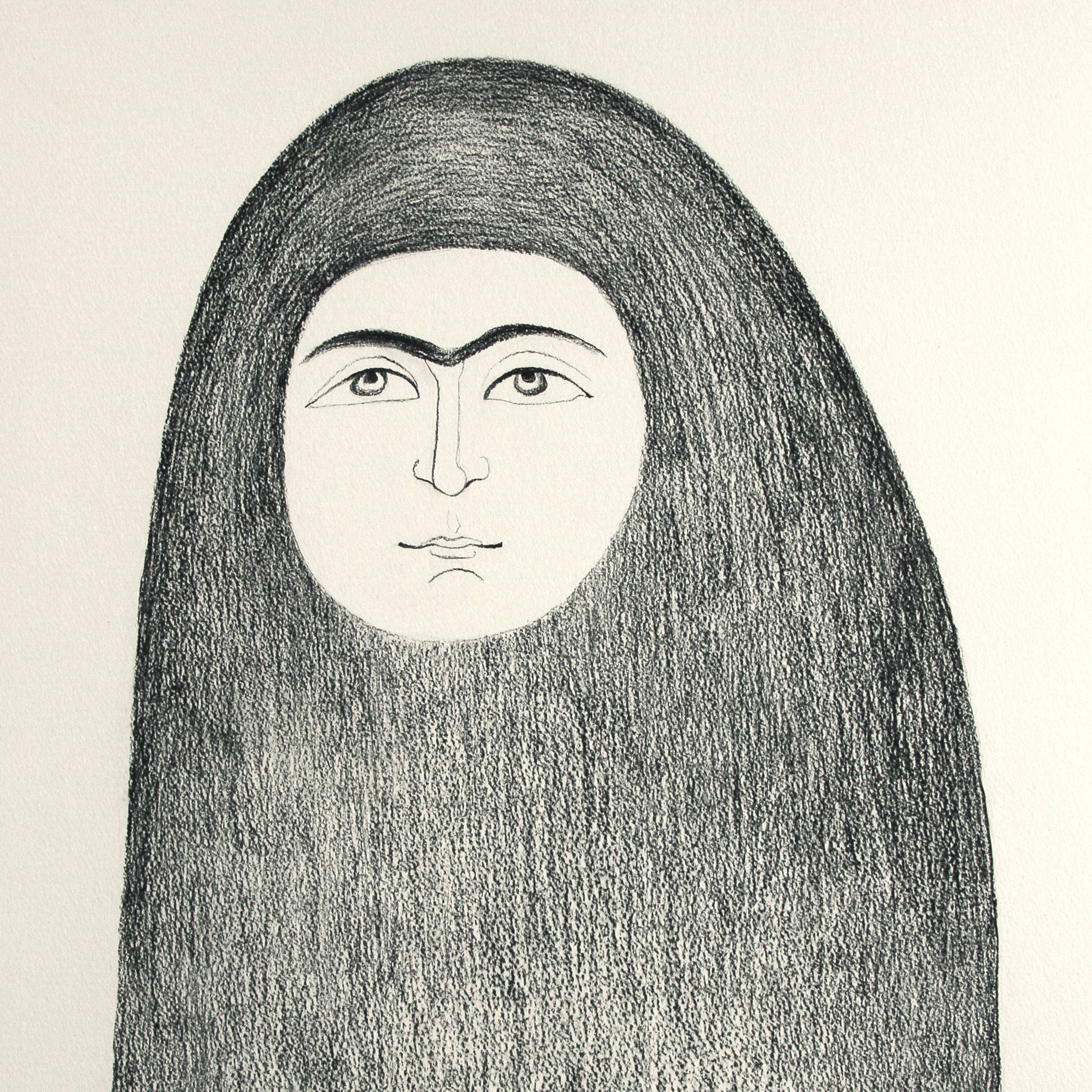

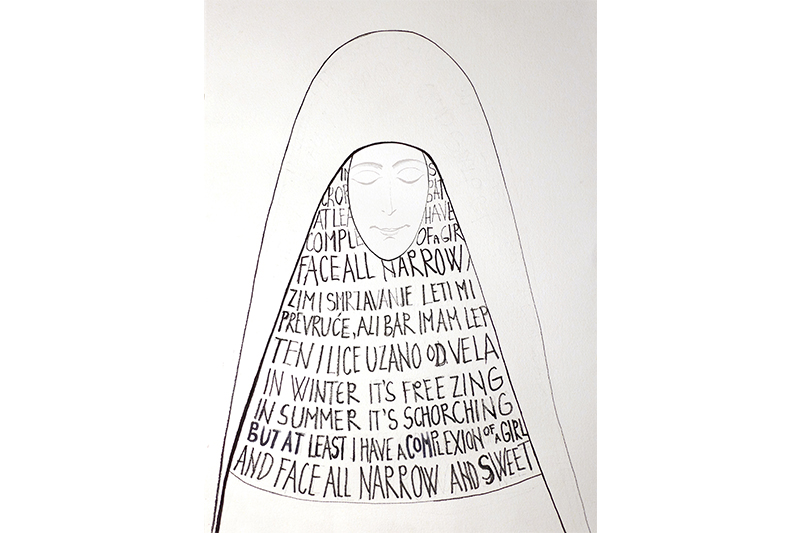

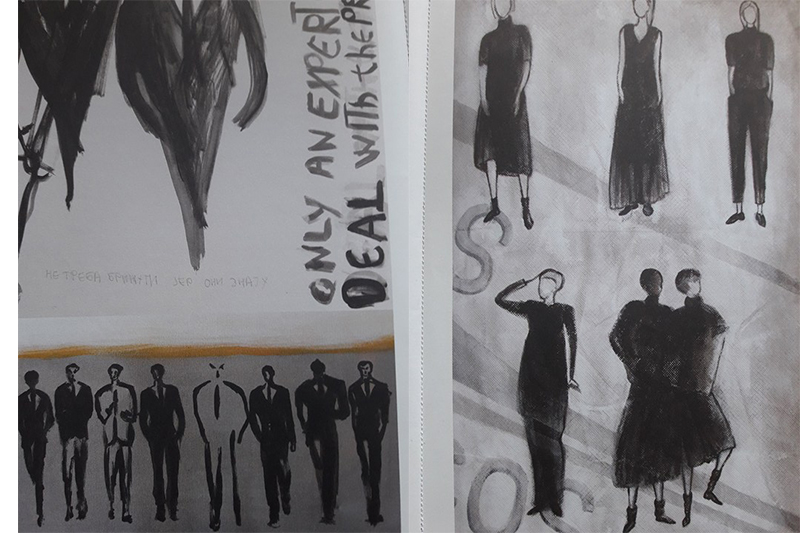

Inspired by her sophisticated figures draped in black religious habits, burqas, business suits, as well as her exceptional spirit and humor shown in her wondrous drawings of monastic life, we talked to the lovely but bold Nada Kovinic about art, black clothes, monasticism, women’s circles..

We’re amazed by your girls in black, how did the public react?

They’re amazed too! Especially other artists, which is strange because we artists aren’t usually so open to other people’s work. Usually it’s the curators, or the critics, or the general public who have the strongest reactions, and the artists just stay indifferent. But my artist friends came up to me just to say how much they loved it. They couldn’t follow up on my work and had no idea what to expect, so they were surprised to see what it all looked like. This is the first time I’ve exhibited this project, although the people who came to the monastery could see it. We had an open studio where we worked on icons, but all of my work could be seen at the convent. They were all over the walls and I’ve gotten good reactions from visitors even then. That’s how I realized they might be interesting to a wider audience.

The Academy and SKC

Ever since I enrolled into the Academy of Arts, I would go to the Student Cultural Centre all the time. Biljana Tomić was a curator there, at the time. She was very open to working with young artist, and my friends and I would often work with her. She would talk to us about conceptuality and got us into this world. I loved avant-garde art and minimalism since the very beginning. Even though we had just started college, Biljana encouraged us to begin working on projects right away.

She pushed us to write down ideas, to take a more conceptual approach to what we do. It was really a great thing to learn, and maybe even more important to me than what I learned at the Academy. She taught us self-observation and self-criticism as a means of getting ideas. It was extremely valuable to me.

But then you took a turn and decided to go to a monastery?

It really wasn’t such a turn. The way I saw it, it was a step further in self-exploration and artistry. I was interested in art in it’s more radical forms. I was never really prone to performances, but it is definitely one of the more extreme ways of blending art and life together, and that was what interested me. I was reading about the aesthetics of different historical periods and I came across a medieval theory in which art is creation and sacrifice and complete dedication. This is what brought me to the monastery, this idea of absolute dedication and blending art and life into one. Art as a way of creating oneself.

Where does religion fit in?

It’s a part of it. It all goes through a relationship with god. I don’t talk about it much in the context of contemporary art because I believe faith and religion are a personal choice. You either have it or you don’t. Many artists today are atheist, and I try to leave the question of religion out of it so my experience and my work could be more widely understood. I am religious, but I don’t think faith is something you can explain or recommend to someone. That’s what they taught us at the monastery too- it’s not something that can be forced, it’s a personal experience. That’s why I don’t speak about it in the context of art.

Your experience of wearing religious habits is so ingrained in your work, which is both very intimate and universal, when considered an uniform. How does this shift of perspective happen, by wearing a garment that marks you in a way, that draws attention?

Your perspective does change. There is an important reason as to why these clothes exist in the first place, and they serve as a symbol of the change you’re making, of a different life. To begin wearing them is a very profound experience. I could not have anticipated just how powerful it is. When I decided to join a monastery, life there made sense to me, but I could not understand why they needed to wear these veils and robes. I wondered why no one thought of something more contemporary, more neutral, modest. It’s what put me off the most. But I was determined to do it and I knew I had to get used to it. When I started wearing it, I felt immense relief. Mostly because I didn’t have to worry about hair, makeup, the way I looked. Everything was settled. You have a few pieces of clothing to take care of, but there’s nothing to obsess over. I was 26 then and quite shy in the way I talked. When you’re hidden behind these clothes, everyone knows you’re from a monastery and the way they approach you changes, you’re protected in a way, and that’s how I began to be more open, more vocal about my opinions. It’s amazing what happens when looks stop being a part of the equation. I’ve felt free.

I would joke with sisters who were close to my age about it, we’d say “Hey, did you do your hair?” (laughs)

Your drawings show that your clothing could be provocative and that it led to some negative experiences outside of the convent?

We had all kinds of experiences. It was hard to wear it abroad. It wasn’t clear whether we were wearing burqas, people would avoid us, give us looks. We were advised to wear visible crosses. The airport was always dramatic- people would shy away from us. And we always stayed longer for searches. But it was somewhat uncomfortable outside the airport as well. We’d always attract views.

But all these other people dressed in black..?

When I was young and just getting into the art scene, I’d wear a lot of black, my style was both alternative and professional, business-like. When I’d look at photos from various world events I noticed that people usually wore tight, black clothing, sometimes designer. I see it as a sort of cultural elitism. Which then trickles down to lower levels, and you can often see people at some local, alternative events dressed in a black suit, whichever one they have.

I once received this handbook called Men in Black, about curatorial practice and how the elite is recognized as people in black.

Are monastic robes a reflection of power and elitism?

There was a sort of surge in popularity of monasticism in the 90’s, and with that popularity came a sort of power. So even in this world I began noticing this moment of “people in black”, being influential and recognizable, a sort of desirable dress code.

Doing these drawings of prominent figures in black I even came across models for some clothing lines that in their minimalism match the clothing of a nun, or a burqa. I also included men in black suit as a representative of power. I questioned how these black clothes can make a person feel important.

You had decided to go to a monastery, and that alone seems truly brave. You stayed there for ten years- which, again, is really brave.

It was supposed to be forever, like a marriage of sorts. The fact that I left isn’t an accomplishment. But it does take a lot of courage and faith and standing up for yourself. You need to know your reasons. I think my story shows that you can indeed change the course of your life. Anything is possible. It gives me a lot of independence.

What about female solidarity, support?

When I just started my studies and was working on my early projects, I used to work with three more artists, and we spent time together hanging out and developing our ideas. Back home I would draw and they would do their work and then we’d meet up and discuss everything, analyze each other’s work, exchange ideas. I was used to being in the company of other women. It may have been amplified with the issues we faced in the 90’s, when there was no money and we were horribly ambitious and wanted to create work that would match what was being created around the world. It seems a bit silly now, because we wanted to imitate what we followed and aspired to. And we found ways, money from parents, donations from big companies, glass factories, private businesses that would help us come through with our ideas. We were all in it together. I had the same feeling cooperation and coexistence in the monastery. It’s what’s beautiful about living in a convent. I am yet to see another system with a greater emancipation of women or with greater importance placed on women’s circles than here. Most of my friends have moved all around Europe, the ones who stayed find it hard to make time for friendship beside work and family. And I do miss sharing my life with women.

Milica's questionnaire