As if anyone can just run away and start a new life! Not everyone has the luxury to search for one’s true self, there is simply no time for that.

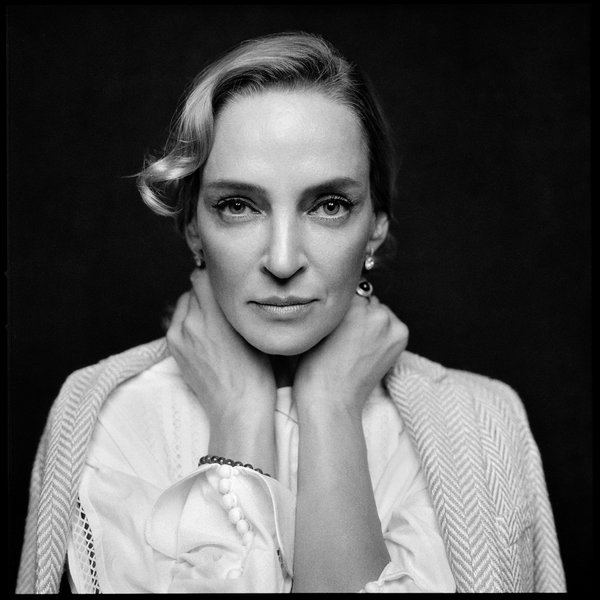

Hana Jušić is a young Croatian screenwriter and director coming from Šibenik, Dalmatian town where she directed her first feature film “Quit Staring At My Plate” (2016). She majored in comparative literature and English language in Zagreb, after which she took up studies in film and TV directing. She has written screenplays and directed several short feature and documentary films, and has been awarded for her work numerous times, at the same time being celebrated as the new-and-upcoming author in Croatian cinema. Her latest achievement, “Quit Staring At My Plate” competed as part of the main selection and won the most significant award at the 45th FEST festival, Belgrade Winner for the best feature. This prize, but also contemporary women’s authorship in the region and what we call women’s film, represents the occasion for talking to forthright and direct Hana Jušić.

How do you feel about being classified into a so-called New Croatian Women’s Wave? This colloquialism has recently encompassed a series of directors from the country you come from as well.

I think that’s absurd (laughs). It seems to me that it happened simply because there were fewer women directors before, and then the need arose for this phenomenon to be named in a certain way. We all wonder how this ‘cut’ happened, how did so many girls start majoring in film directing, and not only that, but they all remain active; they all used to disappear after directing a few student shorts. A group of girls who were more feister about remaining on the film scene undoubtedly exists – that’s the so-called wave we’re talking about, and I belong to that generation. However, all women authors comprising this group are essentially very different.

And anyway, isn’t that in itself discriminatory, a women’s wave? What it means is that it is not our aesthetics or poetics that are being valued, but only our gender quality.

I have once said in an interview that pussy is the only thing that we all have in common, after which I was quoted a million times, with an interpretation that we are starting a revolution. I don’t like the fact that the film community was very much male-dominated before, and then this attribute ‘female’ appeared – it’s like they put us in a ghetto. My only intention was to be taken seriously.

Instead of giving weight to your work, this so-called “positive discrimination” sometimes, unfortunately, simplifies things.

Yes, precisely! In my film, the main character is a woman, and this is very important to me, but there are other contemporary Croatian women’s films which could have easily been made by men. There aren’t so many explicitly female subjects, but I don’t understand the need to call something ‘female’; this in order to classify it in some way, I suppose.

Certain elements could be singled out as shared, and some of them can also be found in your work, like, for instance, the family motif. Nevertheless, yes, I agree, this kind of classification even on a global level seems like an external, artificial, non-cinematic act.

I was a part of a film workshop once – there were sixteen participants, and they split us into groups of four, but they made a point of putting a woman in each group; I didn’t understand what was that about. When I go to festivals, I often hear ‘there are many women’s films’. I mean, of course, I am extremely happy that so many women have the opportunity to create, but I don’t understand why is this constantly emphasized, like we’re incapable or dim-witted (laughs). If certain racial or ethnic minorities were referred to in this way, it would be considered politically incorrect, while for women this still isn’t the case. I know that most people do this with good intentions at heart, but this sort of promotion is something I don’t need.

I’ve heard that after seeing your film some people said they were surprised that a female director made it. Other comments were that it was raw, cruel, and intentionally horrid. I would like to stick to the last comment: you are from Šibenik and you nevertheless made a film which is in complete discord with so to speak ‘picture perfectness’ of Dalmatia.

What is important to me is a kind of decontextualization of the surroundings, that’s precisely it. The sea is almost completely omitted from the film, except in places that are dirty, especially when Marijana and her brother are eating at the main bus station. Cities at sea, which possess this particularly urban quality, take a completely different form. I wanted to depict a huge post-socialist city which makes the sea look perhaps even a bit rotten. Even when the characters go for a swim at the actual beach, in color correction we made sure the sea looked unhealthy. This is not because I wanted to depict Šibenik in a bad light, although this is how the majority reacted; I was merely interested in showing the way the city feels when you live in it, not when you visit it as a tourist, which are two completely different things. I’m tired of Croatia being treated as a tourist Mecca when a lot of things in these cities still do not function as they should.

You’ve chosen to omit the grandeur of the squares and alleys that attract tourists to Dalmatian coast. Everything is somehow wretched, seemingly without history.

Due to tourism as well as the economic boom, Šibenik has been changing in recent years, and the people seem to be almost ashamed of the socialist architecture, discarding it as obnoxious, shameful. I don’t like when tradition is being recreated, when supposedly traditional stone houses are being built – when, in fact, they are made of plastic and consumable materials. Everything is an imitation. It is really fascinating how a mentality of a city can best be seen through its architecture and its changes! So, the part of the city I was interested in was the one ‘behind the scenes’, where people virtually live on top of one another in their living rooms, where everything is heard and seen. I’m exaggerating a little, of course (laughter), but this kind of interpersonal relationships, even life itself, are determined by such clustered, busy architecture.

You are often associated with what is known as the ‘aesthetics of ugliness’, and I can see that there is a continuity of the motifs in your films, i.e. the meat from If A House Was A Good Thing, the Wolf Would Have It and Quit Staring At My Plate. It is interesting to notice how food, which often brings members of a family together and represents a delicate connective tissue of their stability, receives a completely new meaning in your work.

Yes, I totally agree. However, it seems to me that some things sound better and smarter when they are analyzed rather then when they are contemplated or shot on film (laughter). As for the ‘aesthetics of ugliness’, Jana Plećaš, the cinematographer I’ve been working with for a long time, and I have similar tastes and we get along well. She is not just an excellent cinematographer, but also an author in the real sense of the word and I always send her scripts and then we exchange photographs as references. We understand each other perfectly.

And what were the references for Quit Staring At My Plate? In a way, this film could aesthetically be compared to the New Greek cinema.

In my last short film, the reference was Dogtooth (Yorgos Lanthimos, 2009), but I’m not completely satisfied with it. This time we wanted the city to look South American, but not resemble any particular film or scene. In fact, I wanted everything to look like the modernist films of the ’60s, to have almost a documentary feel, like Cassavetes, or something to that effect. I chose a more fluid directorial process because I needed to get close to the characters. We wanted everything to seem more realistic – Jana and I carefully built the apartment where the Petkovic family lived; we put extra effort in showing the accumulation of objects which in time tenants just stop noticing, and in creating this natural, layered feel of piled up things. This apartment is also interesting because it is so dark; there is an unusual tradition in those extremely sunny Dalmatian cities where, due to the heat, apartments are made dark as caves.

There is a practice of making first feature films in native towns of young authors. This has been the case in the region in the last couple of years, at least. What is your relationship with Šibenik? This is the first film you’ve made there.

I have a specific relationship with Šibenik, because I left it early and it is not my city anymore. It is not a type of a hometown when you, for example, go to college somewhere, and then you return home. On the other hand, Zagreb has become visually and cinematically uninteresting to me, and when it comes to the mentality of the people from Šibenik, I am sentimental about it and I want to document it. That’s why I came back.

Perhaps you wanted to get this nostalgia off your chest?

It feels as if this foolish sentimentality has died a little after this film, yes (laughter).

Speaking of sentimentality, at the end of this interview, I would like to ask you about the ending of your film. Your female lead has a kind of a panic-stricken fear from fleeing to Zagreb – which is not a typical crazy metropolis – so she chooses rather to stay in the suffocating atmosphere of her family home. Is this your professional attitude towards the youth from smaller towns?

This partially emerges at an intuitive level. First I wrote this ending because this is also the way I am, to a certain extent (laughter). I don’t find her family unbearable; on the contrary, I like them. In a way, yes, she returns to this hell, and then it is not so bad after all. I wanted to invert what is typical for such films – someone casually leaves home and ultimately finds their place under the sun.

As if anyone can just run away and start a new life! Not everyone has the luxury to search for one’s true self; there is simply no time for that.

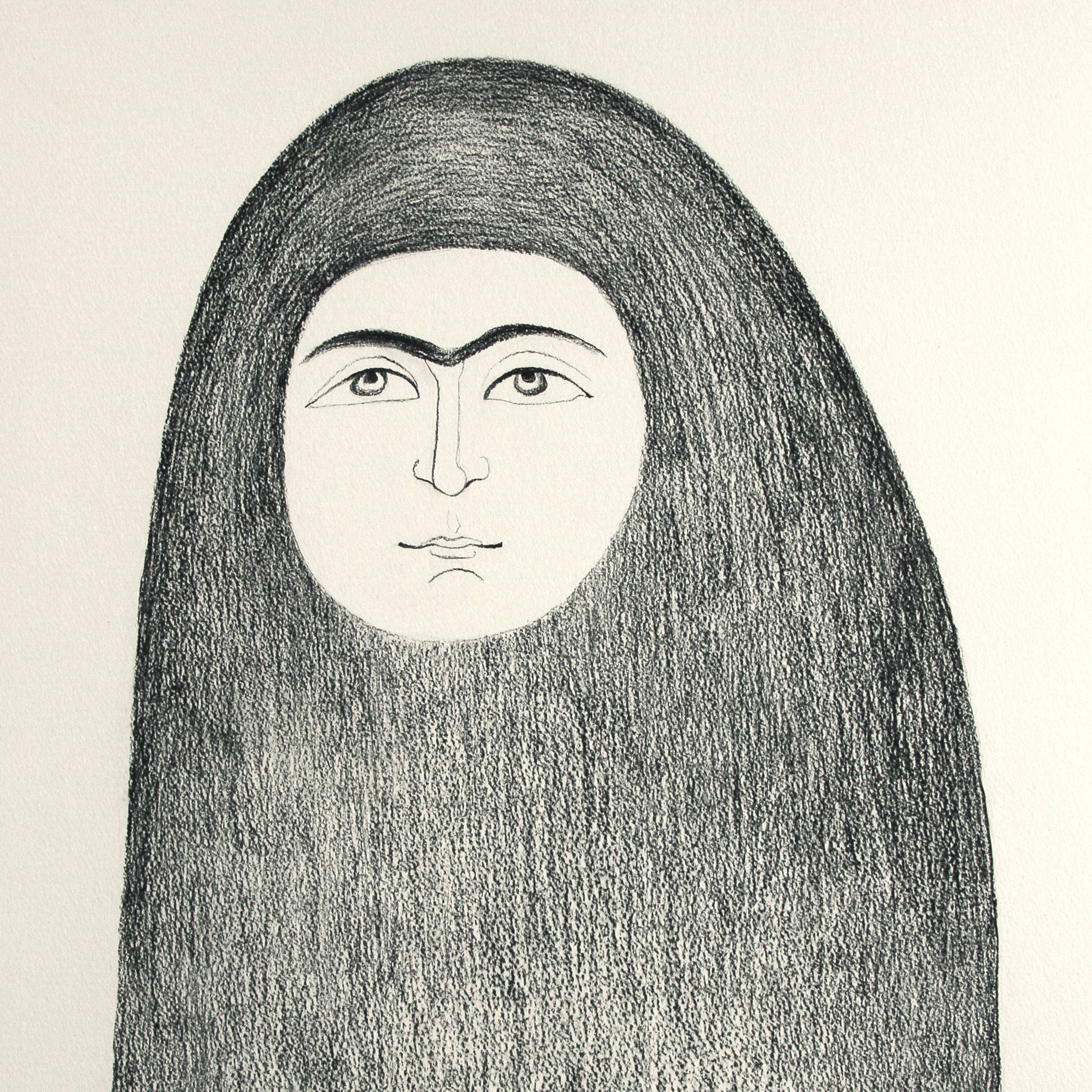

Quit Staring At My Plate, frames from award-winning movie