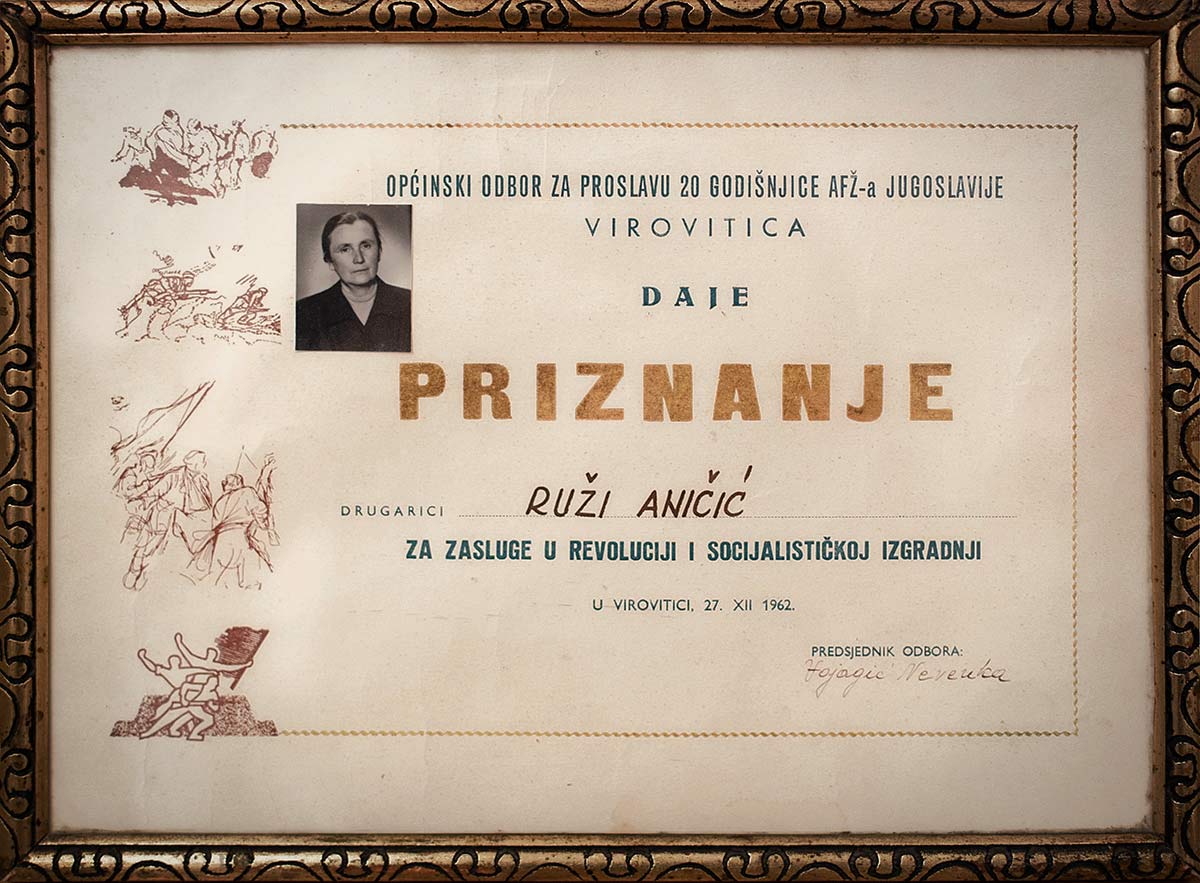

Ever since I was a little girl, I was interest in my grandmother’s CITATION. Placed in an antique frame, the citation for comrade Ruza Anicic was awarded by the Women’s Antifascist Front of Yugoslavia, for her merits in the revolution and construction of socialism.

In a small photo in the corner, grandma looks a bit more strict, her face sharp, but still gently, innocently smiling. The plaque always stood out, hanging on the wall of her apartment, among pictures of saints, a reproduction of Cézanne’s flowers and a drawing she got from my aunt for Women’s day. It just didn’t fit.

It always seemed too important, too serious. When grandma died, the Recognition was the only thing my brother and I fought over. Then we dug out grandpa’s silver swords, and my brother was satisfied.

Since then, I carry it with me wherever I move, find a nice place to hang it, and decorate it with a willow garland every spring, like she used to.

Grandma met World War II with three children in the district of Vitrovica. While her husband joined the partisans, she gathered other women to care for the wounded and help organize the fight against the occupying forces. The Germans killed her father-in-law and burned her house in a raid, so she spent the rest of the war begging for a place to stay.

My grandfather returned from war a hero- with typhus and a severe head injury- and was offered to settle in one of the abandoned houses in Vojvodina. Grandma Ruza chose Srbobran- she said it had a beautiful church.

Though she fought for the revolution, she never steered away from God. The party threatened to kick her out, but grandma stood her ground. Her friend Stana used to tell me they couldn’t go through with it because of her great reputation among women. Her husband died shortly after, along with her daughter who died of tuberculosis. She sent her two sons to school and was left alone. She had a veteran’s pension and a bench in church. She spent time with a group of veterans, visiting memorial sites, and her friends from church- with who she visited monasteries and sang prayers. She had a best friend, Budimir, though I can’t remember if he was a veteran or church friend. Every season, she worked in a cooperative.

She was old and, given her pension, didn’t need the extra money- but woke up early in the morning to work in a field, or a factory, for a modest wage. “If all the other women are going, I’m going too”, she justified her deep-seated sense of solidarity to my father, who was worried for her health. To other women, it was a means of survival. She used the money to give to the church, or Unicef, or my brother and me. By refusing to choose the church or the revolution over each other, in this resistance of exclusion- I think she won her own, autonomous space.From being a believer, to being a fighter, a mother, a wife, a housewife- she always had another self to come back to. Humble and free. She wore a headscarf, dark-colored skirts and blouses, no makeup. She celebrated women’s holidays, Saint Paraskeva and March 8th. She supported every woman in our family. She was insanely proud of my good grades. She was not a particularly good cook, or seamstress. If she picked up a needle, it was to patch up a sock or glove- more out of habit than not being able to afford new ones. She read gospels and prayers, copied them, sang, fasted every Wednesday and Friday. She never read the Bible to me- only fairytales and poems for children. She never made me go to church, although she’d be very happy when my mom would dress me up for a holiday, or the odd Sunday, and sent me to go to service with her. I always had a great time with grandma Ruza. In church, on the way to school, endlessly playing make believe, watching TV. We watched rallies, children’s shows, cartoons before the news…

I was still a child when grandma Ruza died. We never got to more serious topics.